By Tim Hayes

Growing up in a small borough, with its own park, its own theater, its own library, and its own three-block “downtown” business district, we had it made. My friends and I could walk everywhere, see or do or buy anything we wanted, and never break a sweat making it home for dinner on time.

A couple of the favorite haunts during any stroll through the neighborhood shops included the record store – where you could peruse the racks of 45s (we didn’t have the dough for a full-blown album) until the little guy who owned the place started to get sore at us for not actually buying anything – and the hobby shop, where all of the coolest airplane and sports car plastic model sets sat on shelves, just waiting for young bucks like us to take them home.

During one such venture into the hobby shop, for some reason I split off from the fifth-grade formation – went rogue, I suppose – and headed over to a different display of model kits, where one caught my eye and tenaciously held on like an angry pit bull.

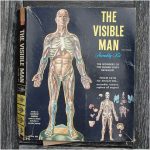

The Visible Man.

The model displayed just what it sounded like – a clear plastic encasement in the shape and form of a grown human male, with every organ, nerve, vein, artery, and bone placed perfectly inside. My imagination fired, creativity inspired, I asked the owner of the store what The Visible Man cost. When they revived me off the floor, I left, dejected, and walked home.

Promoting the high-quality educational value of this model kit to my parents, we arrived at a deal whereby I cut the grass and did some other jobs around the house in exchange for funds sufficient to purchase The Visible Man. And before you knew it, there he was, on the desk in my room. Inscrutable, immovable, impeccable. Just waiting to be assembled into pristine formation.

I mean, how hard could it be? The directions looked pretty clear. And, honestly, how many bones and organs and stuff could actually be in a man’s anatomy? I mean, come on! This was a one-afternoon job for a 10-year-old kid with good grades, tops.

Three weeks later, I’m sitting there with a plastic man who looked like he just got extracted from a 12-car pileup with the Jaws of Life. I couldn’t fit one more thing into this guy’s abdomen, yet I sat there enraged, holding a spleen or a pancreas or a liver or some damn thing. How could there be all these leftover parts? (Little did I know this adventure would serve as a precursor to scores of bookshelf, dresser, and other demented IKEA projects in later life.)

Eventually, I figured the hell with it – my Visible Man would just have to go through life without a liver, or whatever that thing was, and hope for a transplant later.

Then it came time to paint in the veins and arteries. And the wheels really came off. One slip of the paint brush, maybe. You wipe it off and try again. But after about 18 mistakes in – while continuously getting the red veins mixed up with the blue arteries – and that little plastic bastard came THIS close to going in the garbage.

Soon, my Visible Man became invisible, going back into his box and down into the cellar, where bad toys go to die. Seven years later, I left for college and never gave him a second thought. He’s undoubtedly in some landfill today, still waiting for that liver transplant.

Come to think of it, I probably should have gotten The Visible Woman instead. Even if her innards never got assembled properly, at least the outer shell could have kept a fifth-grade boy busy.

Copyright 2015 Transverse Park Productions LLC and Tim Hayes Consulting